How the Settlers Got Around Once They

Arrived

Waterways

The

Erie Canal was completed from Albany to Buffalo by 1825, but a large section of

the canal was completed by July 1820, with boats running from Montezuma to

Utica three times a week. The trip took two days and cost $4.00. Stagecoaches

were available to take passengers to final destinations.[1]

The

Erie Canal served as a funnel for settlers coming from the east. Some stayed

and others passed on through, taking boats on the Great Lakes after arrival in

Buffalo. For the farms and businesses of Central New York, the canal provided a

means of transporting their crops to markets in larger cities and brought goods

to local merchants.

Cato

Four Corners was only eight miles from the Canal. In 1830, some residents

attempted to bring it a bit closer. A bill for the establishment of the “Cato

Canal Company” was read before the State Assembly, and referred to a select

committee.

The

Cato Canal Company proposed to build a canal from Parker’s Pond to the Seneca

River, and lower Parker’s Pond by 4 to 6 feet. The petitioners for the creation

of the company included Abner Hollister, Augustus Ferris, Andrews Preston, John

Hooker, William Ingham, Jacob Drew, Benjamin Conger, John Jakway “and their

associates.” The public notice of their intent in the Auburn Cayuga Patriot indicated that their

proposed corporation had a capital of $10,000, to be increased to $20,000, and

that they would have the right to receive tolls on the canal and to levy a tax

on wetlands “reclaimed or benefitted by the making of the said Canal, equal to the

increase of value thereof.”[2] This plan would have increased farm acreage

and provided new tax revenues as well as providing a means of water transport

directly from the Town of Cato to the Seneca River. Toll revenues would have

paid for the canal’s construction.

Prior

to the application to the State Assembly for the creation of the canal company,

the Auburn Free Press quoted an

editorial from the Weedsport Advertiser that encouraged an idea that

the planned canal should go one mile further and connect with the Erie Canal

near Weedsport. The writer stated, “the ground is extremely favorable for the

enterprise; and the last mile would yield a canal toll equal to all the rest,

-- as it would bring at once into the market the wood, timber, stone, &c.

with which the banks of the Seneca abounds [sic], besides giving to the

citizens of Cato and its vicinity, an easy and direct communication with the

Erie Canal.”

The

writer continued,

Cato

is a fine township of land, is now rapidly improving; her population are

industrious and enterprising; and when the contemplated Canals are carried into

effect, and her roads improved, she will be to this village [Weedsport], what

old Scipio has been to Auburn, its main

spring and most substantial support. We hope therefore to see their

enterprise come to a successful issue, and if they should carry their canal

only to the Seneca, we will endeavor at some future day to meet them on the

opposite shore with the waters of the Erie.[3]

When

the bill was presented to the entire House at Albany, the bill did not receive

the required two-thirds majority of the membership, and the company was

therefore not incorporated. No further record of this proposal has been found,

so it appears that the idea was soon abandoned. [4]

Although

Cato Four Corners only came close to having its own canal, water transportation

was always important to the area. Major roads led both to the Erie Canal and

Lake Ontario. Although the Cato canal effort went nowhere, the plank roads to

the Erie Canal at Jordan and Weedsport, and stage lines running to the canal

and Oswego appear to have met the local transportation needs.

The

Erie Canal continued to be important to Meridian, and its environs, even after

the railroads came along with speedier transportation to distant markets.

The

original canal route changed after the New York State Legislature authorized

construction of the “New York State Barge Canal” in 1903. It was completed by 1916. Locally, that meant that traffic would now

flow along the Seneca River instead the much narrower channel that flowed

through the nearby villages of Jordan, Weedsport, and Port Byron. A canal

terminal was built at Weedsport.

In

order to create a new canal on the river, the river was dredged to a depth of

at least 12 feet, and in some cases, bridge had to be raised to accommodate the

height of canal boats.[5]

Stagecoaches

Stagecoaches

provided public transportation in upstate New York as early as 1797, when a

coach first traveled from Utica to Geneva along the Genesee Road. It took three

days to travel a distance that a modern automobile can now travel in two and

half hours. By 1804, a private company had exclusive rights to provide stage

service between Utica and Canandaigua along the Seneca Turnpike.[6]

Stagecoaches

continued to provide transportation for both passengers and the mail throughout

the region well into the nineteenth century. In 1823, a private stage company

commenced operation, passing through Cato Four Corners on the way from Oswego

to Elbridge:

Mails stage from Utica, through Cato Four

Corners to Elbridge. The subscribers will commence running a stage from Utica

to Cato Four Corners, once a week, on the 3d of December next, which will leave

Utica at every Wednesday at 4 o'clock in the morning and arrive at Hampton

village at Hallock's at 6 o'clock; Humaston's, Vienna at 11 O'clock;

Doolittle's, Camden at 2 O'clock; Hempstead's, Williamstown, at 6 O'Clock; from

thence Thursday morning at 4 O'clock start for Richland and arrive at 8

o'clock; at Mexico 12; New Haven 2 o'clock; at Oswego village 6; and start from

thence Friday morning at 4 o'clock; Cato Four Corners at 12 and at Elbridge at 4.[7]

The

trip took two days and eight hours to travel the seventy-five miles from Utica

to Cato Four Corners, and another four hours for the twelve miles from Cato

Four Corners to Elbridge!

One

driver of the Auburn to Oswego stage was Aaron Kirk, who, in 1912, reminisced

about his lengthy career, which began in 1849:

Talk

about roads! There were no county or state roads in those days at least in

Cayuga or Wayne counties. In the rainy season those roads were simply bogs

through which the horses floundered, mud up to their bellies. In winter we

frequently could not get through because of the snowdrifts and then we would go

to the nearest farmhouse and wait till the storm ended.[8]

In 1911, the stage had a run-in with an automobile in Meridian,

but the car was hurt more than was the stage!

A

rear end collision of an auto and the Meridian stage happened Tuesday evening

on our dark streets. No damage was done to the wagon except to boost it ahead,

but the auto bent a mud guard, and smashed a lantern.[10]

In 1924, Central New York’s infamous winter weather was the culprit,

and this time the stage was the loser:

A fall of eight inches of snow yesterday accompanied by wind

blocked the highways to motor traffic in all directions. The mail carriers were

able to cover only a portion of their routes with horses and cutters. The

Meridian stage tipped over yesterday. This morning it got stuck in a drift at

the Meridian cemetery and was unable to get through. The Lehigh [Railroad] snow

plow went over the line yesterday the first time this season. The trains ran on

time.[11]

It

is unknown if the Meridian stage was motorized by that time, but people still

used horse-drawn vehicles at that time when the roads became impassable to

motor vehicles. This writer’s brother was born during another severe snowstorm

that same winter, and a horse-drawn sleigh was used to fetch the doctor from

Cato to a house on the Federal Road where our mother awaited the birth of her

first child.

By

the 1940’s U.S. Mail trucks were carrying mail to and from Meridian twice each

day, but those trucks were coming from Syracuse instead of from the train at

Cato. This writer’s sister, who worked at the Meridian post office during high school in the mid-1940’s, was able to ride with the mail

truck driver to Syracuse to do some shopping on a few occasions.

Reliable roads became increasingly important as the nineteenth century progressed and the population increased. From Canada came the idea for a new type of road: the plank road. The first one in New York State was built near Syracuse about 1846 by George Geddes, and was used to transport salt.[12] Such roads were built of wooden planks running parallel to the direction of travel and provided a smooth road surface [13] – something much better than the muddy and rutted roads that they supplanted.

Plank roads were inexpensive and

easy to construct. They provided smooth traveling the year round, which

accounts for their popularity. The State of New York had spent massive amounts

of money on canals, which left little for road building, and small towns

couldn’t afford the huge cost of macadamizing local roads. Plank roads provided

an inexpensive solution with the potential to improve economic conditions for

the community as well as for the investors who funded the roads. Dairying

became a more important part of upstate agriculture about this time, perhaps

because of the speedy and smooth travel that plank roads could provide for the

transportation of perishable dairy products.

The building of plank roads by

private companies was usually initiated by the residents of the rural

communities they served, since the benefits of such roads would accrue

primarily to those places. These local investors realized that they were

unlikely to make a profit by building these roads, but the economic benefit to

the community at large overrode such concerns.[14]

As early as 1846, William Smith

Ingham of Cato Four Corners met with a group of gentlemen at a home in Jakway’s

Corners to discuss the possibility of building a plank road from Oswego to

Auburn, via Hannibalville, Ira Corners, Cato Four Corners, Jakway’s Corners and

Weedsport.[15]

The State legislature enacted laws

providing for the establishment of plank roads as private toll roads in 1847.

By 1853, 3,500 miles of such roads had been built by 350 chartered companies in

New York State, including one from Cato Four Corners to Jordan, and another

from Jakway’s Corners to Auburn, which was in use from 1848 to 1877. Traces of

the Cato to Auburn plank road were discovered under Auburn’s North Street

during sewer installation in 1971.[16]

Beneath the Plank Road from Cato to

Auburn, excavators recently found an earlier 20-foot wide “corduroy” road. The

logs, laid side by side in parallel to the route of travel, were cut down

between 1817 and 1818 as part of a route from Oswego to Auburn. Other portions

of this road were found in 1967 under South Seneca Street in Weedsport.

From 1829 onward, this route was

used by stagecoaches. Travelers could expect a 20-hour journey (changing

coaches at Weedsport) between the Lake Ontario port and Auburn.[17]

The plank road from Cato Four

Corners to Jordan (following the eight-mile path of today’s Jordan Road) was

built by the “Cato and Jordan Plank Road Company,” chartered in late 1850.[18]

Names of residents of Cato Four Corners were listed as officers in an 1850

advertisement: G.H. Carr, Michael Ogelsbie, Robert Bloomfield, Charles

Bloomfield and Sardis Dudley.[19]

The office of the company was in James Hickock’s store in Cato Four Corners.

The plank roads that originated

from Jakway’s Corners and Cato Four Corners enabled local farmers to reach

markets more easily, as they connected these villages directly to the Erie

Canal at Weedsport and Jordan, respectively.

As the wood surfaces of plank roads

had a useful life of only about five years, these roads became less desirable

to investors and state laws later permitted removed of the planking. The roads

continued in some cases as toll roads, but eventually reverted to public

ownership. Whether or not anyone made a great deal of money from plank roads is

uncertain, but for a time they provided good routes to markets, benefiting the

communities which they served.

Railroads

Railroads

first came to New York State in 1831 when the Mohawk and Hudson Railway

connected Albany and Schenectady. In 1836, the Utica and Schenectady route was

opened, and other companies started routes further west in rapid succession;

lines from Utica to Syracuse and from Syracuse to Auburn were established in

1839, and Auburn connected to Rochester in 1841. Another route, direct from

Syracuse to Rochester, superseded those two lines by 1852. Rochester was

connected to Batavia and Buffalo by 1842. In 1858, these separate rail lines

were consolidated into the New York Central by Erastus

Corning, permitting easier travel on one railroad from Albany to Buffalo.

In 1938, Ida Hull Applegate of Meridian had a

ticket for one of those early railroads:

Old R.R. Ticket Still Good.

Because of fluctuating railroad rates, Mrs. G.L. Applegate of

Meridian will have to pay an extra 10¢ if she wishes to use a railroad ticket

purchased in 1846 from the Syracuse and Utica railroad.

The 92-year old ticket, issued before the New York Central System

was built, cost $2. Present rates are $2.10. Rail officials say that the

yellowed ticket would probably be honored.[20]

These

private companies were in direct competition with the State’s Erie Canal, and

at first the state did not permit trains to carry freight. In 1847, freight

shipments were at last allowed, but the State required the payment of

equivalent canal tolls (in addition to the railroads’ freight charges) into the

canal’s general fund. This was not popular, and the requirement was removed in

1851. Railroads eventually took over most of the freight being shipped, with

the canal retaining only grain and lumber traffic.[21]

The

coming of the railroad to any town was a cause for celebration. Unfortunately,

the village of Cato acquired tracks and Meridian did not.

The

Railroad Station at Cato

(Photos from the author’s collection)

The

railroad that came was a replacement of the Lake Ontario, Auburn, and New York

Railroad, which never got off the ground, and lost its funding during the Civil

War The Southern Central Railroad’s Articles of Association were filed in

November 1865, and the building of the railroad began. [22] It was completed,

after a number of false starts, in the autumn of 1871, and began shipping coal

from Pennsylvania to the coal dock transshipment point on Lake Ontario at Fair

Haven in 1872.[23] [24]

The

opening day celebration of the completion of the Southern Central to Fair Haven

almost didn’t happen. It appears that a farmer over whose land the railroad

traveled wasn’t happy about having it on his property. It was either because he

felt he wasn’t paid enough for the right-of-way through his property, or

because crossing the track to get to his cornfield was too difficult; both

reasons were testified to at trial. (A descendant of this farmer attests to the

latter). Whatever the reason, William Van Wie of Martville, along with his sons

Jacob and Jerome, removed a section of track. A train filled with two hundred

passengers on their way to the ceremonies at Fair Haven approached to find a

red flag on the track, and stopped. William and Jacob were arrested and taken

to jail in Auburn, while Jerome was let go because he had alerted the train of

the danger with the red flag. The rails were replaced and the train continued

its journey.[25] William and Jacob

were indicted on a charge of malicious mischief and were adjudged guilty in

their trial two years later.[26]

The

railroad provided a route for milk from local dairy farms. A milk station was

built south of the village of Cato.

The

Southern Central Railway’s route to Fair Haven was financed by the Lehigh

Valley Railroad, and was at first called the Southern Central, then the

Southern Central Division of the Lehigh Valley Railroad, and by 1887, just the

Lehigh Valley Railroad. At that time there were three trains each day in each

direction. [27] In

addition to providing passenger service, the coming of the railroad gave

farmers an alternate means of getting crops to market and boosted the economy

of the region.

Southern Central RR

(Image Licensed under CC BY 2.0)

The

railroad at Cato provided transportation south through Ithaca as far as Elmira,

and connections to New York City and Buffalo – all on the same Lehigh Valley

railroad. Passengers could also make connections to the New York Central lines

at Weedsport. “Taking the cars” became a common method of travel for people

from Cato and Meridian, as they went to Auburn on shopping trips and took

picnic excursions to Lake Ontario.[28]

Although

convenient, affordable, and efficient, railroad travel was not without danger.

The Southern Central made big news in February 1884 when a train going south

from Cato fell into the Seneca River at Weedsport due to the collapse of the

first span of the bridge. Three members of the crew were killed: the engineer,

the fireman and the brakeman. Fortunately, the passenger car remained on the

tracks and the passengers escaped without injury. These excerpts of articles

from an Auburn newspaper are especially interesting:

Train Dispatcher

Nelson, sitting in his office at the Southern Central station in this city,

yesterday afternoon, received at 3:45 the tidings of a terrible disaster which

had occurred on his road, twenty minutes earlier, at the Seneca river bridge

less than a mile north of Weedsport. At the hour indicated, a train drawn by

engine 65 and composed of two box cars, a coach and caboose was running toward

Auburn and had reached the bridge. Before it had passed one third of the

distance over the bridge, the engine and two box cars plunged through into the

river, carrying three men to a sudden and terrible death.

… The part which

gave way to let the train through, yesterday afternoon, was the northernmost span.

It sank in such shape that the engine went down backward, leaving the smoke

stack just visible above the water and the two box cars plunged forward into

the chasm. The coach, which contained seven passengers and the caboose, were

left on the track above. Three men went down with the -wreck—Burr Ridgeway,

engineer, John Strait, fireman, and Tim Danahey, brakeman— and their bodies at

this writing have not been found.

… A Weedsport

telegram says that when the train passed on the bridge the conductor looked out

of the window and saw the locomotive and two or three cars plunging into the

river and jumping to his feet, gave the alarm. The passengers rushed toward the

rear door. Once outside, they saw that the first span of the bridge had broken

down, and the locomotive, the tender and two freight cars were almost out of

sight under the ice. The caboose hung from the brink partly in and partly out

of the water and the passenger car still remained upon the track. Only the

smoke-stack and a small portion of the cars, with some timbers of the bridge,

were visible. There were but six or seven passengers on the train. The crash

was heard a mile and a half away.

… The accident on

the Southern Central just north of this town continues to be the topic of

interest and farmers are here from Port Byron and other parts of the county in

great numbers. The river near the scene of the wreck is covered with people and

at times it is feared that the weight of the crowd will be greater than the ice

can bear and that another serious casualty may be the result. Yesterday

afternoon, while two farmers were crossing the ice toward the wreck, the ice

suddenly gave way under them and they went into the water. After a short but

hard struggle they succeeded in gaining a solid footing and returned home quite

satisfied not to witness the operations about the wreck. It is related of one

of the passengers who happened to be in the forward part of the passenger coach

of the fated train and lost his hat at the time of the accident, that seeing his

head-covering floating in the water he waded up to his waist and secured it

after which he returned to the car and changed his clothes for others that he

had in his valise.[29]

The

Lehigh Valley Railroad ceased its service through Cato in 1953. Coal shipments

had ceased much earlier, and the site of the former Fair Haven coal dock became

the location of Fair Haven Beach State Park. Passenger service had been

discontinued in the late 1940’s.

Lehigh Valley Railroad System Map

(Image Licensed under CC BY 2.0)

The arrival of the New York State Thruway was

one of the changes that spelled doom for much of the nation’s railways, as the

construction of expressways began across the US. The Lehigh Valley lost its

ability to connect to the New York Central at Weedsport because of the new

highway, and all the track north of Auburn was eventually pulled up.[30]

While

the Lehigh Valley was still active, there were several attempts to provide some

sort of rail service on an east-west route through Meridian. The Buffalo, Rochester

and Eastern Railroad began to plan a steam railroad across New York State as

early as 1901. The proposed route would have paralleled the New York Central

and would have passed just south of the village of Meridian. [31] A local newspaper

reported in 1907:

Surveyors

for the Buffalo, Rochester and Eastern Rail Road are working in the town this

week. The proposed route will run the railroad through the south end of Cato.

Hold your breath and pray. A good east and west railroad over the proposed

route would enhance double the price of farm lands all along the line. The

Central can't begin to handle the freight offered them and a road would develop

this section to beat the band. This road wants the co-operation of every one

along the line and will get it. Make the dirt fly.[32]

Unfortunately,

the New York Central lobbied heavily against the construction of this railroad,

even though the proposed route was not to compete with the New York Central,

but to serve New England, where most of its investors were located. After

numerous hearings in Albany, the State Public Service Commission refused to

grant a charter.[33] The project was

abandoned.

Two

separate proposals were made to provide electric trolley lines through

Meridian. In 1899, Wallace Tappan of Baldwinsville proposed that the Syracuse, Lakeside,

and Baldwinsville Railway be extended westward through Meridian to Cato and

possibly as far west as Wolcott. That road would have traveled slightly north

of the village.[34]

In

1910, a similar proposal for electric railways passing through Meridian and

Cato was brought forth by a group of people in Wolcott.[35]

Public

transportation in Meridian was provided only by the Cato and Meridian stage

until its demise. Once the Lehigh Valley ceased passenger service, there was no

local means of travel other than the automobile until the early 1960s, when

Trailways bus lines provided service to Baldwinsville for a brief time.

Passengers from Meridian could travel on to downtown Syracuse via bus to the

old DL&W (Delaware, Lackawanna & Western) terminal.

Ferries and Bridges

Getting

across other waterways was a problem for early travelers through Central New

York, so ferries and bridges were often set up where they were needed. For

example, there was a wooden bridge across the northern end of Cayuga Lake as

early as 1800, built by the Cayuga Bridge Company, which had been chartered

three years before. This remarkable structure cost the grandiose sum of $25,000

to build – and it was over one mile long.[36]

Travelers

didn’t always have such an easy time of crossing waterways. Many resorted to

fording streams at shallow places, as did the Ferris family at Baldwinsville.

At many fords, enterprising early settlers began ferrying people across rivers.

No

matter how good the roads, early residents of the Town of Cato needed to cross

the Seneca River with some regularity, at first to access the main east-west

routes, and by 1822, to get to the Erie Canal, about eight miles south. From

early days, there were three ferry crossings: one in the southeast corner of

the Town of Cato to Jordan, in the Onondaga County Town of Elbridge, another at

Weedsport, and a third in between.

There

was a ferry across the Seneca River to Jordan at the southeast corner of the

Town of Cato, run by Solomon Woodworth[37], who lived there

in a log house.[38] Mr. Follett operated another ferry where

Route 34 now crosses the river between Cato and Weedsport. Between those two

ferries, Henry Abrams’ ferry service helped people cross the river where the

Bonta Bridge now stands.[39]

Crossing from Cato to Jordan

By 1816, Joel Northrup had built a

floating bridge over the river to Jordan, at the site of Woodworth’s ferry.

[He]

was induced to embark in this enterprize[sic] by an expectation, that the

accomplishment of so desirable an object to the people in that vicinity would

enable him to procure by subscription a donation or reimbursement for all

expenditures; that he has been disappointed in this expectation, and that

although the said bridge cost him two thousand dollars, yet he has received

only eight hundred dollars…the said bridge is of great utility to the public,

particularly to the inhabitants in that vicinity.

A bill was introduced in the New York

Senate to authorize him to raise $1,200 by charging tolls to cross the bridge. [40]

Northrup died in 1820. The float bridge

remained. Whether or not he ever managed to collect tolls is unknown, but by

1834, some local people gathered to plan for the maintenance of the float

bridge:

At

a meeting of several the inhabitants of the towns of Cato & Ira held at the

house of P.P. Meacham on Monday the 26th of May 1834 for the purpose

of taking measures for keeping in repair the Floating Bridge across the Seneca

River.

Resolved

that in our opinion it is advisable to circulate in Cato, Ira, Victory,

Conquest, Hannibal a subscription for sums to be paid yearly for the repairs of

said Bridge.

Appointed

George Hoskins, Wm. Hedger & Josiah Converse commissioners to oversee &

pay for all necessary repairs & who shall draw their order on the treasurer

for the same & who shall make an annual report to the treasurer of their

proceedings.

Appointed

P.P. Meacham Treasurer who shall make and keep a correct account of receipts

and payments which shall be open to inspection at all times and who is

authorized to pay over all monies to the said commissioners.

Appointed

the town collectors of the several towns to collect from their several towns

& who are hereby authorized to received 5 per cent on their collections

& pay over to the treasurer the sums by them collected & take his

receipt therefor.

In

case of vacancy or complaint of either of the officers above mentioned the

vacancy to be filled by the inhabitants of said towns, notice to be given by

either of the commissioners of the time & place of said meeting.

Appointed

Sardis Dudley & Luther Barnes to circulate the subscription in the several

towns.

Now

therefore We the subscribers inhabitants of the said towns of Cato, Ira,

Victory, Conquest & Hannibal, do agree to pay the sums set opposite our

several names each and every year for the purpose of keeping in repair said

Floating Bridge to be paid to each of our town collectors at the time we pay

our taxes.[41]

Further along in the account book is a

list of over 260 residents of the five towns, pledging amounts from twenty-five

cents to one dollar. The 1853 map of the Town of Cato shows a toll gate at the

north end of the crossing.[42]

In 1840, the New York Assembly passed a

bill to incorporate the “Cato and Jordan Bridge Company.”[43] No bridge

resulted, however.

The float bridge was still around in 1856,

when it floated downstream and had to be brought to its proper place.[44] The following

year, the bridge had to be lowered two feet after the new channel was dug at

Jack’s Reef, which changed water levels.

In 1859, a serious accident was reported

at the float bridge:

On

Wednesday of last week, as a family who were moving from Jordan to Ira, Cayuga

County, were crossing the Float Bridge over Seneca River, the horses, from some

cause, became frightened just as they reached the north end of the bridge, and

backed the wagon, containing thirteen persons varying from six months to sixty

years of age, off the upper side of the bridge into the river. The horses freed

themselves from the wagon, and did not get into the river. Fortunately,

assistance soon arrived and the unfortunate family were all rescued, although

not until some of them were nearly drowned. One little girl floated down partly

under the bridge where she could not be seen, and where she remained until all

the others were helped out, when, it being found there was one still missing, a

search was instituted and she was found and taken out, apparently lifeless, but

after long and active exertion was restored to consciousness. – Jordan

Transcript.[45]

The

bridge made the news again in 1861, when it was reported that it “went

adrift…but was fortunately secured at Busby’s steam sawmill. For several days

passengers and teams had to be ferried across the river in a boat; but the

bridge was at last brought back to its proper position and secured, and teams

are again passing over it as before.”[46]

In

1862, the locals had had enough. In December of 1862, the Board of Supervisors

of Onondaga County met and discussed the need to do something about the river

crossing between Cato and Jordan:

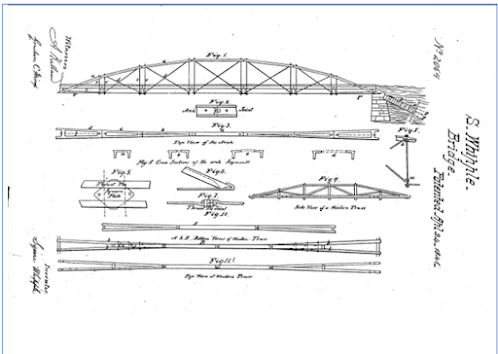

Resolved,

That the interests of this county and the county of Cayuga require the

construction of a good and substantial bridge across the Seneca river, at or

near the point known as the Float Bridge, near Jordan; that the present float

bridge having been condemned by the Commissioners of Highways of the towns

adjoining as being unsafe and unfit for use, and beyond economical repairs; and

that this Board will appropriate the sum of seven thousand dollars, which sum

is one-half the amount required in the construction of a bridge of iron in

accordance with the plan herewith exhibited (and known as Whipple’s patent,)

including piers and abutments and superstructure, said bridge to be as well

constructed in all respect, both as to workmanship and material, as the bridge

recently built by Degraff & Jones across the Genesee river…in the city of

Rochester.[47]

Albany

was paying attention, and a new bridge was authorized by an act of the state

legislature in April of 1864. The State authorized Onondaga and Cayuga counties

and the Towns of Elbridge and Cato to raise $5,000 each via bond issues for the

building of the iron bridge, “where the present float bridge is now located.” [48] A request for

“Sealed Proposals” was published.[49] Shortly

afterward, it was announced that “the contract for constructing the new iron

bridge over the Seneca river, in place of the old float bridge, was awarded to

Mr. Simon Degraff of Syracuse, for $12,700. There will be two spans in the

bridge of 150 feet each.”[50]

As

construction progressed, local newspapers kept everyone well-informed:

The

work of putting up the iron bridge, which is to take the place of the old float

bridge…was commensed[sic] this week. When completed, it will be appreciated by

every one who has passed over the road within a dozen years.[51]

The

new iron bridge over the Seneca River…is nearly completed, and will be ready

for the passage of teams, we understand, next week. Everyone who has seen the

bridge pronounces it a splendid one.[52]

The

new iron bridge over Seneca river is completed, and will shortly be “opened”

for travel. It is the largest structure of the kind in the world, total length

365 feet, width 24 feet, height of arch 24 feet, composed of two spans each 180

feet. Height of pier from bottom of river 41 feet, total weight of bridge over

25 tons – The old float bridge having performed in office for over thirty years

[sic], became water logged and somewhat dangerous.”[53]

Two years

later, the State set a speed limit for the bridge: “No person shall wilfully

[sic] ride or drive over the said bridge faster than a walk.” A fine of

twenty-five dollars was set as the penalty for speeders who violated the rule. [54]

Seneca River Iron

Bridge - S Degraff, Builder Length 373 Feet - Geo. H Dygert, Artist.

(Photo courtesy of William Havens)

This

bridge design was not new. In 1840, Squire Whipple of Utica had patented the

design of the “bowstring truss,” which used cast iron ties to strengthen the

arch and even out the load that the arch had to sustain. It was the first cast

and wrought iron bridge in the United States. [55]

This

design became the standard for bridges built across the Erie Canal after the

first one was built across the canal in Utica in 1841 (it stood until 1922,

when the canal was closed after the opening of the Barge Canal).

The

Whipple bridge became the standard bridge design for the Canal by 1848 and

thirty bridges were built. He sued for patent fees totaling about $2500, but

eventually managed to get less than half of what he felt he was owed.

By

the time the Degraff bridge was built from Cato to Jordan, Whipple’s patent had

been expired for two years. [56]

In 1884, the Groton Bridge company was

contracted to replace the Degraff bridge,[57] By 1895, this new bridge had been pronounced

unsafe. The Owego Bridge Company removed the 1884 bridge and sent it upstream

to “add it to the Bonta bridge.” [58]

In 1924, the Towns of Elbridge

and Cato voted to replank the bridge with “3-foot long-leaf yellow pine either

8” or 10” wide and 18 feet long, with a center rail the length of the bridge;

the same to be bolted down to divide the traffic.” Each Town was to pay half the

cost and was also receive half of the old bridge’s planks.[59]

The 1895 bridge was replaced in

1951, and was most recently rehabbed in 1985.[60]

The 1895 Iron Bridge in the

early 20th century (Photos from the author’s collection)

The 1951 bridge today (Photo

from the author’s collection)

Abrams’

Crossing / Bonta Bridge

Henry

Abrams arrived in 1805, settling near the current site of the Bonta Bridge at

the intersection of Bonta Bridge and Blumer Roads.[61] He kept a ferry

there for many years. The 1853 map of the Town of Cato shows a landowner named

C.B. Bonta just north of the crossing, presumably the origin of the bridge’s

name. A tollgate is also indicated on the map.[62]

There

was a bridge on the site before 1834, when a Seneca Bridge Company was

organized “to erect a bridge across the Seneca river, commencing on the north

side of said river, on lot number forty-three, in Cato, (formerly Brutus,) near

the house of David Ward, running south across said river to the south bank, in

the place of the former bridge…” David

Ward, Phineas F. Wilson, and Abner Hollister were appointed commissioners,

authorized to accept subscriptions to the stock of the corporation. Once the

bridge was built, the corporation was authorized to erect a toll gate and

collect tolls:

for

every wagon, cart or other carriage drawn by two horses, oxen or mules, twelve

and a half cents, and for every additional horse, ox or mule, three cents; and

for every wagon, cart or other carriage drawn by one horse, ox or mule, six

cents; for every sleigh or sled drawn by two horses, oxen or mules, six cents;

for every sleigh or sled drawn by one horse, ox or mule, four cents; for every

horse and rider four cents; for every horse, mule or jack led or driven, three

cents; for every score of cattle, horses or mules, twelve and a half cents; for

every score of sheep or hogs, six cents; for every person on foot, two cents.

Toll

evaders were to be charge eight times the appropriate toll, and could be sued

for it. Toll collectors were forbidden to delay anyone crossing the bridge, or

to charge more than the legal toll. Such infractions could assess a fine of

five dollars against the miscreant “toll-gatherer.” When the bridge was

completed and “in a safe state,” operating a ferry or building another bridge

within a mile of the Seneca Bridge Company’s bridge, was to be unlawful. Other

rules set a standard crossing speed (not faster than a walk) and the number of

cattle driven across (a maximum of twenty).

The

law setting up the corporation set a two-year time limit for the erection of

the bridge.[63] By 1853, the law

organizing the Seneca Bridge company was repealed.[64],[65]

It’s

unknown when the bridge was finally built, but one certainly existed by 1857,[66] as the Canal

Commissioners included it in a list of locations where channel excavations were

planned, to accommodate lower river levels after the new channel had been cut

around Jack’s Reef.

During

that period, truss bridges made of wood were the most common, which were easy

to build and put in place. Many bridges of this type were covered, to protect

them from weathering, and it may be assumed that the first Bonta Bridge, unlike

the Float Bridge to Jordan, was a covered bridge.

In

1868, a proposed law came before the New York Assembly “to authorize a special

town meeting in the towns of Brutus and Cato…to determine relative to the

rebuilding of the Bonta bridge in said county, and a bridge between Brutus,

Mentz, and Conquest.” Whatever building plans there were for the Bonta Bridge, those

plans disappeared when later in the same session the act was amended to remove

references to Bonta Bridge, and the act became “an act to authorize the

building of a bridge between Brutus, Mentz, and Conquest…”

During

that same session of the Assembly, the future of the crossing appears to have

been in real peril, as an Assemblyman “presented three protests against

abandonment of the Bonta bridge, which were read and referred to the committee

on roads and bridges."[67] The Town of Cato instructed the highway

commissioners to repair the bridge, building “at least one stone abutment and

two if necessary.”[68]

A

rebuilt bridge, this time of steel, appears to have materialized in the 1880’s,

according to testimony about Seneca River bridges in 1911. A lawsuit between

the Lehigh Valley Railroad and the State Canal Board, concerning the railroad

bridge at Weedsport, included the testimony of G. Boardman Whitman:

I

should the think the clearance of the Bonta Bridge was eight feet now. It was

built about fifteen years ago, perhaps eighteen. It was rebuilt sometime in the

eighties. It was an old bridge taken from north of Weedsport…and this was a new

bridge built by the Oswego Bridge Co. It is a steel bridge. A wooden bridge was

there before that bridge was put there. I don’t know when the wooden bridge was

put there; the last time it was rebuilt, it was carried away by high water once

or twice and then rebuilt two or three times before the steel bridge was put

there…there has been continuously a highway bridge there, except for during

such times as it may have been washed away by a freshet or something of that

kind.

Town

of Cato minutes shed some light on what happened. On June 13, 1885, the town

boards of Cato and Brutus met at Bonta Bridge to discuss the bridge. Present

were Levi Hamilton, supervisor of Brutus, who chaired the meeting, and L.A.

Colton (Cato Town Supervisor), C, Morley (Clerk of Cato), J.S. Morley, F.M.

Hunting, John Bell, and William Church (Justices of Cato), Bachelor, D.C.

Knapp, Rude (Justices of Brutus). “The Brutus Hwy Commissioner asked for an

Appropriation and recommended the Groton Iron Bridge Co.’s plan for an Iron

Bridge costing $6,500.00. The Cato Commissioner recommended the repairing of

the Bridge at a cost not to exceed one thousand dollars for which a vote was

taken…” Colton, Morely, Hunting, Church,

Bell, Knapp voted for repairs. Hamilton, Bachelor, and Ride voted for a new

iron bridge.[69]

In

1888, the Town Boards of Brutus and Cato met again, this time at the Weedsport

Iron Bridge. They consulted with the representative of the bridge company. They

determined that “it is apparent that the guarantee has not been fulfilled.

Resolved that the commissioners notify the Contractor or Bridge Builders that

the Towns require the fulfillment of the contract so that the Bridge shall be

what by the terms of motion made that the Bridge Company be given two weeks to

decide on the term or what they will do in regard to the fixing the bridge

before attempting to replank the bridge. Carried. Adjourned.” [70]

All

of these details seem to indicate that an iron or steel bridge was built at

this crossing in late 1880’s, although definite details of this construction

have yet to be discovered.

The

bridge issues were raised again in September 1890, when the towns of Brutus and

Cato met again to consider “the repairing of the approach to the iron bridge

known as Bonta Bridge on the south end of said bridge. A motion was made and

carried that the commissioners may not exceed $500.00 in repairing and

gravelling said road and that the expense to be borne jointly and equally by

the two Towns but that each Town bear the expence[sic] of its own officers.”

The vote was 6 to 4 in favor of the motion. In October, the two boards

appropriated additional funds of “$500.00 or mor as is needed but not to exceed

$500.00” to complete the work. [71]

Issues

continued. Cato Town meeting minutes in early

1891 declared,

whereas

the approach or roadway on the southside of the bridge crossing the Seneca

River between the Towns of Brutus & Cato known as Bonta Bridge has been

made impassible and useless for large portions of several previous years and

particularly so during the past year by the matter of said river crossing and

running over said roadway to a considerable depth by reason of the filling up

and shallowness of the channel of said river that the said roadway is now

covered with water and cannot be used for travel – be it therefore resolved

that the legislature of the State be requested to enact a law and make suitable

appropriation for cleaning out and deepening the channel of said river in such

place or places as may be necessary for the carrying of said water or conveying

the same so that it will not interfere with the proper use of said roadway and

approach and be it also resolved that the Town Board of the Town of Cato be and

are are hereby empowered to take such action as is necessary to secure such

legislature[sc]. The above passed unanimously with the proviso that the same be

done at State expense.[72]

The

Town Boards of Cato and Brutus met August 19, 1895, to consider building a

bridge on the causeway south of the Iron Bridge. A vote was taken to build an

iron bridge. The wording of the minutes seems to indicate that the bridge at

that time was of two parts – iron on the north span, and wood on the south. A

motion was made to “contract with some good and reliable Iron bridge builder to

build the wood part of the bridge with a new iron bridge after receiving

estimates to be submitted to the joint Town Boards for approval.” The motion

was carried.[73]

On

August 25, the two Boards met once more and the highway commissioners made a

presentation. They had “made a contract with the Owego Bridge Co. for an iron

bridge to be put on the north[sic] end of the old iron bridge in place of the

wood part of the bridge, length about 160 feet for the sum of 3,100 dollars all

complete and painted.” That contract was rescinded, and the boards eventually

agreed to

contract

with the Owego Iron Bridge Co. to build an iron bridge on the crossway south of

the old iron bridge at the place aforementioned to be 38 feet long and 14 feet

wide for the sum of $600 according to the specification made by the company to

the Commissioners and in the contract they are to level and put in shape the

Iron Bridge known as the Weedsport Bridge and to paint the same all for the

above specified sum to the satisfaction of the Highway Commissioners of the two

towns and are to have no pay on the contract until the Weedsport Bridge is

completed according to the contract made with the Commissioners.” The inclusion of the Weedsport Bridge created

some issues for the Weedsport Bridge itself.[74]

On

September 25, another Brutus and Cato Town Board meeting took place in

Weedsport to consider a new Iron Bridge to be built over the Seneca River near

the village of Weedsport, using the old bridge, or parts of it, to finish the

Bonta Bridge.[75] On September 30,

both boards voted unanimously to execute the contract with the Owego Bridge

Company. Then, the highway commissioners made a claim that the current bridge

could be made level and made safe for less money, so it was decided to employ a

civil engineer to examine the bridge. If the engineer said that the bridge was

unsafe, then the Owego Bridge Company contract could go forward.[76]

The

1895 bridge project that replaced the Jordan bridge (see above) used parts of

the 1884 Jordan structure, added to the “new part of Bonta Bridge.”[77] It still had

flooding issues, making it totally impassable from time to time, as did the

other bridges over the river, many of which were eventually raised to deal with

flooding and improve navigation on the new Barge Canal.

In

1901, the Cato Town Board, in conjunction with the Town Board of Brutus,

appropriated $350 to install railings on both sides of the road at each end of

the bridge and to grading and filling the roadway. They also authorized the

highway commissioners to ask for bids to paint the bridge.[78]

By

1910, a contract was let to an M. Fitzgerald to build a new bridge.[79] “A new structure

with a clear span of at least 150 fee over the Barge canal channel, with the

remaining spans made of the most economical length” was recommended. The bridge

was completed in 1912, [80] and repainting

took place between 1916 and 1920.[81],[82]

At

the same time the Cato and Elbridge Town boards planned to replank the Jordan

bridge, the Cato Town Board met with their colleagues from Brutus at the Bonta

Bridge to do the same for the Bonta Bridge. They voted to use “2-inch long leaf

yellow pine, to be lengthwise of the bridge as joint construction and each to

do their share and each Town to stand ½ the expense and each Town to submit

figures on the above material and buy where they can to the best.” A couple of

months later they determined that “Brutus to do the work and furnish the needed

materials and send to the bill to the Town of Cato so they pay ½ of the bill.”[83]

A

rehabilitation of the bridge took place in 1952[84], and another was

scheduled for 2014, when the bridge was closed for repairs.[85] Work was planned

most recently for the 2018 construction season, when the bridge was to be

repainted and steel to be replaced.[86]

Bonta Bridge in

2022 (Photo from the author’s collection)

Follett

Crossing / Weedsport Bridge

David

Follett was licensed to operate a ferry across the Seneca between Cato and

Weedsport in 1807, so for next fifteen years, the locals crossed the river this

way.[87]

In

1820, an act was presented to the New York Assembly, authorizing “The Seneca

Bridge Company formed by inhabitants of Cato, Brutus, and Aurelius to build

toll bridge over the Seneca River. [88] The bridge to

Weedsport, presumably a wooden bridge, probably covered, was erected in 1822.[89] The group

assembled to build the bridge consisted of John Jakway, Augustus Ferris, Abner

Hollister, Elihu Weed, and Walter Weed.[90]

The bridge at

Jack’s Reef, downriver from the three Cato bridges, in the early 20th

century.

The early wooden

bridges across the Seneca from Cato were certainly similar to this one.

(Photo from “Jordan

Memories” – a digital online photo collection - https://jordanmemories.omeka.net/items/show/166, accessed 13

August 2022.)

The

1853 map of the Town of Cato shows a toll gate at the north end of the

crossing.[91]

There

are newspaper accounts that the bridge at Weedsport was raised and repaired

after the southern end of the bridge “settled mightily” in 1888. The Groton

Bridge Company performed that work.[92]

A

single-span iron bridge was authorized in 1896.[93] The bridge was important. That spring the

road on each side of the proposed bridge was two to three feet underwater and

the new bridge was only a few inches above water. The Bonta Bridge, as well as

the Mosquito Point and Free Bridge, were also under water.[94]

During

its construction, there was controversy over who would pay for it. The Town of Cato Highway Commissioner William

Hallett was determined that the Town was not going give $9,000 to the Owego

Bridge Company for its share of the $18,000 cost. The Town of Brutus refused to

pay more than its half. There was an

election scheduled early in the year in Cato, and the voters overwhelmingly

agreed with Hallett, in a vote of 181 to 44 against paying for it.

The

justification for it all was that there had been two contracts between Cato,

Brutus, and the bridge company in August.

Later on, Brutus entered into a third contract for the rebuilding of the

Weedsport bridge and extensive repairs of the Bonta Bridge. Cato was not part of the third contract, and

Judge Wm. E. Hewitt wrote an opinion that Cato was not liable to pay, saying that

had the work of the two previous contracts been performed, the work “would have

left these bridges in good substantial condition and safe for travel.” The $18,000 cost of the third contract was

more than four times the cost of the previous two.[95]

The

1896 bridge continued in service, although not without serious issues. In 1903,

the State Legislature authorized major upgrades to the Erie Canal system,

creating the Barge Canal. These efforts continued until 1918. Part of the change was to take advantage of

the Seneca River as an alternative to the old canal that ran through the local

villages of Jordan, Weedsport, Port Byron, and others.

When

the Barge Canal was created, now using the Seneca River instead of the old

channel, the Weedsport bridge was among those that had to be raised. The state

was responsible for the work, and things went badly.

The

bridge had to be raised eleven feet to meet the canal’s requirements. The

bridge was closed for several months in 1910, and had finally been reopened early

in 1911. In February of 1911, the north

abutment, a large concrete slab of several hundred tons, fell several

feet. Newspaper articles blamed the

incident on the removal of old piles in the riverbed, which was done at the

direction of the Barge Canal department. The ferry which had been in use during

the previous closure, again went into service.[96]

By

August, the bridge was still under reconstruction, and people were complaining.

Weedsport was especially upset as people were going elsewhere to do business.[97]

The

bridge finally reopened early in November after having been raised ten feet. Later in the month, Syracuse headline read,

“Big Bridge Falls, Over Seneca River. Structure 270 Feet Long Swings Around

Several Feet. State to Blame, It’s Said.”

The bridge settled, the new concrete abutments (built over the previous

ones) disintegrated and the entire bridge moved several feet westward at 2:00

am on November 25.[98]

Eventually,

the bridge was repaired and opened. By

1925, the bridge was replanked, as had been the Jordan and Bonta bridges a year

earlier. A joint meeting of the Boards of the Towns of Cato and Brutus was held

at the bridge and it was decided that “the bridge be planked a little better

than half way with 2x4x20 ft. long leaf pine dipped with creosote…the two

approaches be given a coat of oil and chips and all places that need it to be

fixed with cold patch before being given the coat of oil and chips…to buy from

the lowest bidder11,000 feet of …pine to be delivered at the bridge.”[99] The cost to the

Town of Cato ended up being #385.00.[100]

It

stayed in place until it was replaced in 1964 by a steel-stringer/multi-beam or

girder bridge.[101] A crack in the

beam of this bridge was repaired in 2014.[102]

The 1896 Weedsport

Bridge prior to 1964.

(License: Creative

Commons Attribution-Share-Alike (CC BY-SA)

Private

Transportation - Foot-Powered

The Ladies of the Wheel (Image: Public Domain)

The

bicycle came to Meridian as it did to the rest of the country in the 1880s and

1890s. The advent of the bicycling craze gave a new liberty to both children

and women.[103]

The

Cato Citizen pondered this newfound freedom:`

Only

a few years ago the burning question was debated “what shall we do with our

girls?” Reams of paper and tons of ink were wasted printing theories and

formulating codes for the discipline of girls and just then someone invented

the bicycle and the question solved itself. The bike became a living issue and

the girls straddled it and rode away.[104]

Bicycles

were in the news with some frequency:

Ira Carl of Weedsport, called on us Monday.' He is selling pianos on a

bicycle. This is the newest use that we have heard for that machine.[105]

Chick Acker hired a bicycle of Theo. Joroloman[sic] Sunday and was to be

home with it Monday and has not returned yet.[106]

The

use of bicycles led to the passage of village ordinances:

A bicycle ordinance has been passed by the [Meridian] village board to

prohibit riding on the walks after seven o’clock at night and in the daytime

the footman has the preference of the walk. This is something that has been

needed for a long time. [107]

The

village of Cato’s bicycle ordinance was a bit stricter:

[Cato]Bicycle

Ordinance.

Riding

upon the sidewalks of this village upon any bicycle or other vehicle is

prohibited. Any person or persons riding upon a bicycle or other vehicle upon

any of the sidewalks of this village shall be liable to a fine of not to exceed

$5 for each offense. This ordinance to take effect on and after May 17, 1897.[108]

Meridian bragged about how many cyclists

there were in town: “We have 64 fine bicycles in and about Meridian. We propose

for a parade of riders some fine evening.”[109]

As

with horses, and later, automobiles, the safety bicycle wasn’t always safe, and

they occasionally caused some injuries.

As

Eddie Wise was going home from Meridian on his wheel, he took the sidewalk, as

usual, and collided with Mr. Lamont, an aged gentleman, throwing him from the

walk, hurting him quite badly, while Eddie sustained a broken collar bone.

Legal proceedings will be the outcome.[110]

______

Herman Stoll had the misfortune to lose one of his

fingers fooling with a bicycle last week.[111]

Private

Transportation – Horse-Powered

For

the first hundred years or so of village history, horses provided the power to

move people and goods around.

Bad

roads made it difficult on occasion. In 1895, a Mr. Burns asked the Town for

his horse, killed will driving on the highway “caused by the bad condition of

the road in consequence of the snow bank not having been properly cleared.”

After considering the statement of witnesses,

“the Board decided that the Town was not liable.”[112] Mr. Burns sued the town, and apparently won.

The Board instructed the Supervisor to appeal the suit and appropriated funds

to pay the costs of the suit.

Although

slow and steady, horse-drawn conveyances were not always safe, as illustrated

in several newspaper articles:

Meridian,

Sept 14. Abram Terpenning’s [sic] team ran away with him yesterday. He was

thrown out, but pluckily secured the horses and drove on to Cato. He is a man

of years.[113]______

Mr. Baker, while

unloading a can of milk at the butter factory at Meridian, was thrown from his

wagon by his horse becoming frightened and was very badly bruised; he is

getting around again. ______

Mrs. Jas. Halstead was driving through Meridian when her horse became

unmanageable and ran away, throwing Mrs. Halstead from the carriage and

breaking her arm. [114]______

A

serious accident occurred to Mrs. Applegate, wife of Charles Applegate, Jr., of

Meridian on Thursday last. She and her husband were coming into the Village of

Meridian with a team before a democrat wagon, drawing a grain drill behind it.

As they came over the hill on the east side of the village the horses became

frightened and by a sudden spring broke some part of harness and became

unmanageable. In the fright Mrs. Applegate feared being thrown from the wagon

and jumped out striking so forcibly that she broke both bones of the right limb

a little above the ankle. Mr. Applegate escaped

without injury.[115]

Private Transportation -

Automobiles

When

the automobile appeared, Meridianites were early adopters. Duryeas,

Oldsmobiles, Reos and Ford Model A’s were on the road before 1906 when the Cato Citizen reported that, “Meridian is

greater than greater New York. New York has one automobile to every 1000

inhabitants, while Meridian has one to every 115 inhabitants.”[116]

A wag

responded in a subsequent issue: “Meridian

may have the ‘Autos’ but Cato has one thing that Meridian can't boast of and

that's Jakway's Sanitarium.” [117]

The

next year, the Cato Citizen told its

readers that “Meridian has four automobiles and Cato hasn't any. Score one for

Meridian.”[118]

Meridian’s

love of the automobile flourished. In 1905 F.L Smith was selling cars in the

village. An advertisement in the Citizen lured

customers by saying “Anyone

contemplating purchasing a Touring Car or Runabout should not fail to

investigate the merits of the R.E.O.”[119]

It was

news when an automobile came through town, and when Dr. Lang was looking at

automobile catalogues, that, too, made the local paper.[120] Dr.

Lang’s perusal of those catalogs was apparently successful, for he placed an ad

in the Citizen: “FOR SALE — Either

one of two good, fearless horses to make room for automobile. Dr. Lang. Phone

30-1 a.”[121]

When locals took

car trips, even just to Syracuse, it made the news. “Mr. and Mrs. E. S. Everts

took a trip to Syracuse by automobile, being away Saturday and Sunday.”[122] Motor trips

further afield were attempted and Meridian’s love of cars grew.

Once the

automobile arrived on the scene, things would never be the same.

The Cato Citizen reported as early as 1899 that there was a

distinct economic advantage to automobiles:

It is now

demonstrated that an automobile vehicle can be driven over long distances and

all sorts of roads at an average speed of fifteen miles an hour, and over good

roads at a speed greater than that of the fastest freight trains. It is also

demonstrated that this work can be done at a power-cost so small as to be

scarcely calculable. One dollar has furnished the power necessary to make a

journey of 707 miles. This is less than it would cost to feed and care for a

pair of wagon horses for a single day.

In

the same issue, the Citizen also

indicated that “the automobile accident has taken its place among the

casualties of civilized life.”[123]

The

local papers began to report accidents:

Mail Carrier Calkins had quite a

thrilling experience one day last week, as he was going up the hill by the

butter factory in Meridian. He climbed the hill on slow speed. On reaching the

top he slowed down to change to the other gear. His batteries were not strong

and before the batteries began to spark, the car backed down the hill at a

terrific rate into a telephone pole and was smashed. The occupants escaped

without injury.[124]

______

Party of Four Had Narrow Escape

When Auto Turned Turtle

Cato,

Sept. 16.-Mr, and Mrs. Dwight Bowen of Meridian and their guests, Mr., and Mrs.

J. W. Devlin of New York City, had a narrow escape from serious injury

yesterday morning, when Mr. Bowen's automobile turned completely over in going

down Meacham's Hill a short distance east of Meridian on the State road.

The

party had started for the State fair and Mr. Bowen, in leaning over to adjust

something, lost control of the steering apparatus. He gave the wheel a quick

turn and the machine turned turtle. All the party were bruised and it is feared

that two of Mr. Devlin's ribs are fractured. The machine was but slightly

damaged and returned to Meridian under its own power.[125]

______

Crashed Into Rig

Five Injured in an Accident Near Meridian

Cato Man’s Nose Broken

And Mrs. Eugene De Forrest's

Shoulder Was Dislocated-

Auto Badly Damaged.

Cato,

Oct. 21.—As a result of an automobile accident a mile and a half out of

Meridian last night, William Van Horn of this village had his nose broken and

face badly lacerated, while four others who were with him in the automobile met

with minor injuries. Van Horn and Chester Stahl, of Lewisburg, Pa., who has a

position in the Lehigh Valley depot here, and two young ladies from Weedsport

were out for an auto ride with Bennie Kimiski. According to the report, in

rounding a turn in the road, another automobile was met. The lights of the

second machine dazzled the eyes of Kimiski who failed to observe a rig ahead in

which Mr. and Mrs. Eugene De Forrest were riding.

The

automobile crashed into the rig, completely demolishing it. Mr. and Mrs.

DeForrest were thrown out, sustaining severe bruises and Mrs. De Forrest

suffered a dislocated shoulder.

When

the crash came, Kimiski and Van Horn were thrown out, Van Horn going head first

through the wind shield and landing on his head. His nose was cut and broken,

and his left cheek torn open.

Young

Stahl suffered a scalp wound, one of the girls had her face bruised while

Kimiski and the other girl escaped without injury.

Dr.

A. J. Spire of Meridian was called and attended the injured.

Jasper

Wands of Meridian went in his auto to the scene of the wreck and removed Van

Horn and Stahl to their homes in the village and also took the girls to

Weedsport.

The

party had been pleasure riding and had telephoned from Baldwinsville to a local

restaurant ordering supper.

The

automobile was badly damaged. The machine was owned by Mrs. Annie Kimiski, a

Polish woman residing South of Cato. Her son, Bennie, has been driving the auto

all Summer. It is reported that the auto was going about twenty-five miles an

hour when the accident happened.[126]

Accidents

between autos and horses, like the one above, were common in the early days of

the automobile.

An unknown

autoist, rounding the corner leading to Meridian, at breakneck speed, Tuesday

morning, barely missed colliding with a horse and buggy coming this way. As it

was, he lost control of his machine which swerved first to the east side of the

road and then went crashing through the guard rail on the west side.[127]

In 1922, a local who was disgruntled

with the lack of driving courtesy wrote to the Citizen: “May I have space to make a few comments? Automobile

accidents are still too common. While driving to Meridian and back Saturday

evening I met twenty automobiles and dimmed my lights for each one. Not one

returned the courtesy.[128]

Newt Ferris recounted the tale of his father’s trip

to Syracuse to buy the family’s first auto, a Reo touring car. The salesman

drove the car to the outskirts of the city, got out on the running board and

advised Edgar as he slid over to the driver’s seat, “If for any reason this

machine stalls on you, or cannot climb one of the hills on the way home, for

Lord’s sake, don’t try to restart it, but roll it to the side of the road, set

the brake, and find someone who can drive a car to get you home.” Somehow, despite the hills on the way home

(especially the one just east of Plainville), he made it home, negotiating the

Calkins Road hill to his home. He had his wife, his mother-in-law and his son

get in and they headed west to Victory, managed to turn around and head back. A

mile from home, the Reo stalled and wouldn’t start up again, so Newt and his

father walked home to retrieve a wagon, a chain, and a team of horses to tow

the recalcitrant vehicle home. Newt’s mother and grandmother refused to ride

with Edgar again.

The saga didn’t end there. The next day, Newt’s dad

managed to crash into a tree while exiting the driveway, and it took a team of

horses to set things right. Finally, at day’s end Mr. Ferris drove the car into

the barn they were planning to use a garage. That barn was fortunately solidly

built because the new driver didn’t hit the brake in time and crashed into the

back wall. The car and the barn both escaped damage.[129]

Over a hundred years after the first autos arrived

in Meridian, automobiles have become an integral part of our daily lives. No

longer a novelty, cars have become a necessity in our busy lives. Whether or

not they will continue to use gasoline-powered internal combustion engines a

hundred years from now is open to question. Vehicles powered by natural gas,

solar or electricity are likely to be the vehicles of the future.

[1] Grant, J. Lewis, “Early Modes of Travel

and Transportation,” Collections of

Cayuga County Historical Society, Number Seven, Auburn, NY: 1889.

[2] “Notice,” Auburn (NY) Cayuga Patriot, unknown date in April

1828.

[3] “Cato Canal,” Auburn (NY) Free Press, unknown date in January

1828.

[4] State of New York, Journal of the Assembly of the State of New

York at their Fifty-Third Session, Albany, NY: E. Croswell, 1830.

[5] “More on the Barge Canal,” Lock

52 Historical Society of Port Byron NY, http://www.portbyronhistorical.org/2018/05/more-on-the-barge-canal.html, accessed 11 August 2022/

[6] Gable, Walter, Miscellaneous Information about Seneca

County, 26 April 2010, http://www.co.seneca.ny.us/history/Misc.%20Info%20About%20Seneca%20County%20rev%203-4-04.doc

[7] Slosek, Anthony, “Stage Coach

Cause for Celebration,” The Oswego County

(NY) Messenger, 19 March 1984.

[8] “Veteran of the Road,” Auburn (NY) Semi-Weekly Journal, 25

October 1912.

[9] “37 Years’ Service,” The Auburn (NY) Citizen, 1 July 1909.

[10] “30 Years Ago,” The Cato (NY) Citizen, 1 October 1941.

[11] “Locals,” The Cato (NY) Citizen and Tri-County Advertiser, 21 February 1924.

[12] Majewski, John; Baer, Christopher

and Klein, Daniel B., “Responding to Relative Decline: The Plank Road Boom of

Antebellum New York,” The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 53, No. 1 (Mar. 1993), pp. 106-122

[13] Plank Road, Wikipedia, 19 April 2010, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plank_road

[14] Majewski, John; Baer, Christopher

and Klein, Daniel B., ibid.

[15] “Auburn and Oswego Plank Road

Meeting,” Auburn (NY) Journal, 14 December

1847.

[16] “Workers Unearth Old Plank Road on

North Street,” Auburn (NY)

Citizen-Advertiser, 23 September 1971.

[17]In Weedsport, State Museum trying

to locate more of 200-year-old wooden road.” Auburn (NY) Citizen updated

13 October 2020.

[18] “List of Plank Roads in New York,”

Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_plank_roads_in_New_York accessed 25 August 2021

[19] “Notice…Cato and Jordan Plank Road

Company” Syracuse (NY) Daily Times, 10

January 1850.

[20] “Old R.R. Ticket Still Good, “Livonia (NY) Gazette, 28 April 1938.

[21] Ellis, David M., Frost, James A.,

Syrett, Harold C., Carman, Harry J. in cooperation with the New York State

Historical Association, A History of New

York State. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1967.

[22] Archer,

Robert F., A History of the Lehigh Valley

Railroad – The Route of the Black Diamond, Berkeley: Howell-North Books,

1977.

[23] Sant, Raymond T., Fair Haven Folks and Folklore, Clyde,

NY: Erie Park Press, 2002.

[24] Archer, Robert

F., ibid.

[25] “Diabolical Attempt To Throw a

Train Off The Track,” Syracuse (NY) Daily

Courier, 1 December 1871.

[26] “Court Record,” Auburn (NY) Weekly News, 4 December 1873.

[27] “Many Trains Served Village,” The

Cato (NY) Citizen, 31

October 1940

[28] Applegate, Sarah Adelia Van Doren,

Diary, 1898, manuscript

[29] “Three Drowned,” Auburn (NY) Weekly News & Democrat, 21 February

1884.

[30] Archer, Robert F., ibid.

[31] “Surveys for Trans-State Steam

Roads,” Cato (NY) Citizen, 1907,

unknown issue.

[32] “Local News,” Cato (NY) Citizen, 1907, unknown issue.

[33] “Refusal of Petition Benefits

Public,” Utica (NY) Herald-Dispatch, 14

August 1911.

[34] “Extension is Feasible,” Syracuse

(NY) Post-Standard, 13 October 1899.

[35] “The Electric Line to Wolcott,”

Syracuse (NY) Post-Standard, 8

February 1910.

[36] Cayuga County Historical Society, History of Cayuga County New York Compiled

from papers in the archives of the Cayuga County Historical Society, with

special chapters by local authors from1775 to 1908, Auburn, NY: 1908.

[37] Storke, Elliott, History of Cayuga County, New York, Syracuse,

NY: D. Mason & Co., 1879.

[38] “Private Canal Journal, 1810,” Campbell’s

Life & Writings of DeWitt Clinton, New York: Baker & Scribner.

1849.

[39] Finley, Howard J.,

"Weedsport-Brutus: A Brief History," Weedsport Library website, 23

April 2010, http://www.flls.org/Weedsport/titlefinley3.html

[40] Journal of the Senate of the State

of New York .... United States: n.p., 1816.

[41] Notebook of Parsons P. Meacham,

1834, unpublished manuscript in the collection of the CIVIC Heritage Museum.

[42] Geil, Samuel, F. Gifford, & S.K. Godsalk, 1853

Cayuga County, NY, Land Ownership Wall Map. Philadelphia, 1853.

[43] Journal of the Senate of the State

of New-York, at Their Sixty-third Session, Begun and Held at the Capitol, in

the City of Albany, on the Seventh Day of January 1840. United

States: E. Croswell, printer to the state., 1840.

[44] “Hard Work to Travel Over Jordan,”

Buffalo (NY) Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express, 5 May

1856.

[45] “Accident at Float Bridge,”

Syracuse (NY) Daily Standard, 2 May 1859.

[46] “Accident to Float Bridge,”

Syracuse (NY) Daily Journal, 15 March 1861.

[47] “Board of Supervisors,” Syracuse

(NY) Daily Courier, undated issue, December 1862.

[48] State of New York, Laws of the State of New York, Passed at the

Eighty-Seventh Session of the Legislature, Albany, NY: Van Benthuysen’s

Steam Printing House, 1864.

[49] “Sealed Proposals,” Syracuse (NY) Daily

Courier and Union, 10 June 1864.

[50] “Jordan News,” Syracuse (NY) Daily

Journal, 17 June 1864.

[51] Auburn, (NY) Daily Advertiser, 7

January 1865.

[52] Auburn, (NY) Daily Advertiser, 4

February 1865.

[53] Auburn, (NY) Daily Advertiser, 15

March 1865.

[54] State of New York, Laws of the State of New York, Passed at the

Eighty-Ninth Session of the Legislature, Albany, NY: Lewis & Goodwin,

1866.

[55] “Whipple Cast and Wrought Iron

Bowstring Truss Bridge,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whipple_Cast_and_Wrought_Iron_Bowstring_Truss_Bridge, accessed 22 February 2022

[56]

Griggs, Frank, Jr., Dist. M. ASCE, D. Eng., P.E., P.L.S. “The Whipple Bowstring Truss,” Structure

Magazine, January 2015.

[57] Fair Haven (NY) Register, 10

October 1895.

[58] Elmira (NY) Star-Gazette, 4

November 1894.

[59] “Minutes of the Town of Cato,”

June 15, 1924, part of the collection of the Civic Heritage, Cato, New York.

[60] "Erie Canal Bridge"

Bridgehunter, https://bridgehunter.com/ny/onondaga/4433140/

[61] “About Cato and Its History,” Cayuga

County New York, https://www.cayugacounty.us/477/About-Cato-Its-History. Accessed 22 February 2022.

[62] Geil, Ibid.

[63] Laws of the State of New York,

Passed at the Fifty-Seventh Session of the Legislature, Albany (NY): E.

Croswell, Printer to the State, 1834.

[64] Rodenbeck, Adolph

Julius., Roberts, Charles O.., Clark, Charles

Hopkins. The Statutory Record of the Unconsolidated Laws: Being the

Special, Private and Local Statutes of the State of New York from February 1,

1778, to January 1, 1912, Prepared Pursuant to Laws 1910, Chapter 513, and Laws

1911, Chapter 192. United States: J. B. Lyon Company, state

printers, 1911.

[65] Documents of the Senate of the

State of New York. United States: E. Croswell, 1853.

[66] “Report of the Canal

Commissioners,” Transmitted to the Legislature February 2, 1857. Albany (NY) C.

Van Benthuysen, 1957..

[67] Journal of the Assembly of the

State of New York. Volume II, 1868.United States: n.p., 1868.

[69] “Minutes of the Town of Cato,”

June 13, 1885.

[70] “Minutes of the Town of Cato,” September

17, 1888.

[71] “Minutes of the Town of Cato,”

October 5, 1890.

[72] “Minutes of the Town of Cato,”

February 20, 1891.

[73] “Minutes of the Town of Cato,”

August 19, 1895.

[74] “Minutes of the Town of Cato,”

August 26, 1895.

[75] “Minutes of the Town of Cato,”

September 25, 1895.

[76] Minutes of the Town of Cato,”

September 30, 1895.

[77] Fair Haven (NY) Register, 10 October 1895.

[78] “Minutes of the Town of Cato,” May

25, 1901.

[79] Annual